… as Graham Parker used to sing, back in ’76, around about the time I exchanged chalk and a metaphorical mortar board for an electronic typewriter and an equally metaphorical Colt .45. A decade earlier, it was late night listening to John Peel, the Beatles and Otis Blue, and I was living in the centre of Nottingham – Castle Boulevard – and driving out each day across the Erewash to teach in Heanor. To be more precise, Langley Mill. The post in which I describe meeting up again with two former pupils from that school and that time has aroused more interest than most.

Since that meeting, one of the pair, Mel Cox, has written about his memories of those days and, with his permission, I’d like to quote from his letter here:

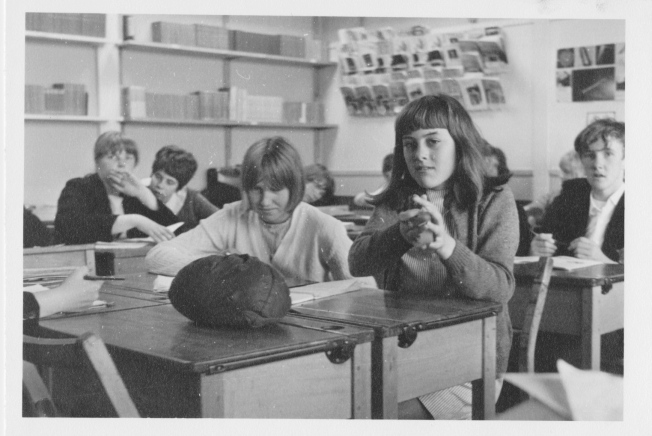

Although lots of us in 216 were ordinary young adolescent kids at the time, just becoming aware of the opposite sex, pop culture, and the swinging 60’s we were undoubtedly still products of the austere 1950’s.

But then along comes this brilliant teacher, whose class is a safe place to be, and who listens to our opinions. He gives us a confidence and self-esteem. He introduces us to modern poems and stories in understandable language. He gets us to want to act in class dramas, and puts on ‘Androcles and the Lion’ and ‘The Business of Good Government’ as whole school plays. He publishes school magazines with our creative work in them. He organises poetry evenings, and sends off for us for copies of the class bible ‘The Mersey Sound’. He takes us on trips to the theatre, and marks our folders in enviable green-ink calligraphy.

Not only that, he plays us ’Lovely Rita’ ‘Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds’, ‘A day in the Life’ and ‘Silence is Golden’ in form time. To parochial working class Derbyshire kids, whose parents all shopped at the Co-op, here was someone who looked like something out of Carnaby Street (or the Bird Cage at least). Corduroy Jacket, PVC mac, flowered shirt, knitted tie and Chelsea boots. We sort of revered him, though we’d never have admitted it. And he was ours you see, and that was really the coolest thing.

I still remember the day almost all of the class left Aldercar in July’67 to go to Heanor Grammar School, and I know that he was leaving that day too. The very last night of term a busload of us went to see ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’ at Nottingham Playhouse. Back at school everyone was saying their goodbyes, some for the summer, some for good. I was choked. The whole 216 adventure had ended, and as form captain he gave me this bitter-sweet memento, ‘Paroles’, by Jacques Prévert.

I felt that the clocks should have been stopped, and that school would never be any fun again.