I first became aware of Jane Freilicher through her presence in Frank O’Hara’s poetry: Interior (with Jane); Chez Jane; Jane Awake; To Jane, and in Imitation of Coleridge. I didn’t immediately know that she was a painter, one of several whom O’Hara befriended, supported, reviewed and who became poetic muses in his verse. Grace Hartigan – For Grace, after a Party – was another; as was, perhaps most famously, Joan Mitchell, in Poem Read at Joan Mitchell’s.

Painter Among Poets was the title of Freilicher’s last, 2013, show at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery in New York; Poet Among Painters, the title of Marjorie Perloff’s 1977 critical biography of O’Hara. New York Poets: New York Painters. The Scene.

When she was eighteen, Jane Niederhoffer, as she was then, eloped with jazz pianist Jack Freilicher, whom she married and later divorced, having met, through him, the saxophonist Larry Rivers when both men were playing in the same band. Freilicher occupied herself during band rehearsals by sketching and painting and Rivers, interested in both Freilicher and her artistic talents, followed suit. It was the painter Nell Blaine who suggested the pair sign on to study with Hans Hoffmann at the Arts Students League of New York. That would have been in 1947.

During the next couple of years, she met O’Hara and the other leading poets in what came to be termed the New York School – Kenneth Koch and John Ashbery and, a little later, James Schuyler. All four men were familiar with the art scene, all, save for Koch, regularly wrote art criticism and reviews, and O’Hara was actually employed at the Museum of Modern Art. There is some small confusion over to which of them she sold her first painting, Ashbery or O’Hara.

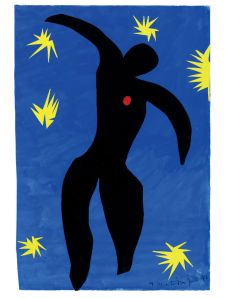

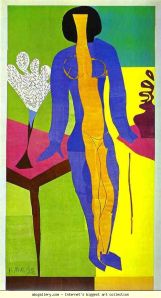

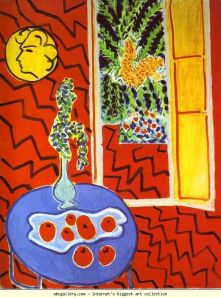

By the early 1950s, she was fully immersed in the New York Scene and had met fellow artists Joan Mitchell, Grace Hartigan and Helen Frankenthaler, all three of whom were attempting to negotiate a stylistic space for themselves amidst the often aggressively male Abstract Expressionism that was the predominant fashion at the time. Strongly influenced by the Bonnard exhibition at MOMA a few years previously, and aware also of the work of Vuillard and Matisse, Freilicher’s riposte to abstraction was a lyrical, light-diffused and vibrantly coloured series of still lives and landscapes that remained at the heart of her work from her first solo show at Tibor de Nagy in 1952 until her last.

Keeping out of fashion, she suggested, gave her the chance to have the freedom to fool around.

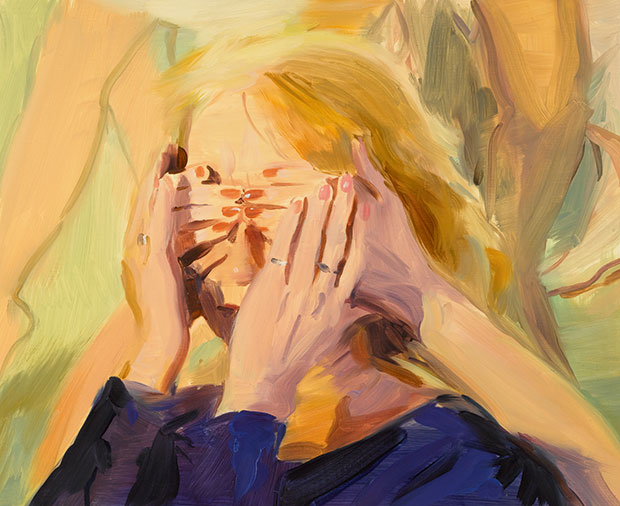

I’m quite willing to sacrifice fidelity to the subject to the vitality of the image, a sensation of the quick, lively blur of reality as it is apprehended rather than analysed. I like to work on that borderline – opulent beauty in a homespun environment.

She also said …

I suppose I think more in terms of colour than of line …

… a statement I used as an epigraph to my novel In a True Light, which is, in part, about the New York scene and Greenwich Village in the 50s, though the character of the painter in the novel is more like an amalgam of Mitchell and Frankenthaler than Freilicher herself.

And, finally, here are the last lines from a poem by James Schuyler, Looking Forward to See Jane Real Soon.

Jane, among fresh lilacs in her room, watched

December, in brown with furs, turn on lights

until the city trembled like a tree

in which wind moves. And it was all for her.